A few nice component manufacturing company images I found:

Window panes. HDR version – 3 images combined here. Abandoned Barber-Colman factory in Rockford, Illinois

Image by slworking2

History of the Barber-Colman Company

Historically one of Rockford’s largest manufacturers.

Began with the founding of the Barber & Colman Company in 1894 – partnership between Howard Colman, an inventor and entrepreneur, and W. A. Barber, an investor. [Today he would probably be considered a venture capitalist.] Colman’s first patent and marketable invention was the Creamery Check Pump used to separate buttermilk and dispense skimmed milk.

Colman’s textile production inventions led the company on its rapid rise as a worldwide leader in the design and manufacture of diversified products. Specific items designed for the textile industry included the Hand Knotter and the Warp Tying Machine China. Through these innovations, Barber & Colman was able to build its first plant on Rock Street in Rockford’s Water Power District, and to establish branch offices in Boston MA and Manchester, England.

Incorporated as Barber-Colman in 1904 and built 5 new major structures on their site by 1907.

Later innovations for the textile industry included an Automatic Winder, High Speed Warper and Automatic Spoolers. By 1931, the textile machinery division had branch production facilities in Framingham MA; Greenville SC; Munich, Germany; and Manchester. This part of the business flourished through the mid-1960s but then declined as other divisions expanded.

Branched out from the textile industry into machine tools in 1908 with Milling China Cutters. Barber-Colman created machines used at the Fiat plant in Italy (1927) and the Royal Typewriter Co. outside Hartford CT. By 1931, the Machine China Tool and Small Tool Division of Barber-Colman listed branch offices in Chicago, Cincinnati and Rochester NY.

As part of its commitment to developing a skilled work force, Barber-Colman began the Barber-Colman Continuation School for boys 16 and older shortly after the company was founded. It was a 3-year apprentice program that trained them for manufacturing jobs at Barber-Colman and paid them hourly for their work at rate that increased as their proficiency improved. The program was operated in conjunction with the Rockford Vocational School.

To foster continued inventions, an Experimental Department was established with the responsibility of continually developing new machines. A lab was first installed in 1914 and was divided into two parts – a chemistry lab to provide thorough analysis of all metals and their component properties, and a metallurgical lab to test the effectiveness of heat treatment for hardening materials. Innovations in the Experimental Department laid the groundwork for the company’s movement into the design and development of electrical and electronic products, and energy management controls.

BARBER-COLMAN became involved in the electrical and electronics industry in 1924 with the founding of the Electrical Division. First product was a radio operated electric garage door opener controlled from the dashboard of a car. Unfortunately, it was too expensive to be practical at the time. The division’s major product in its early years was Barcol OVERdoors, a paneled wood garage door that opened on an overhead track. Several designs were offered in 1931, some of which had the appearance of wood hinged doors. This division eventually expanded into four separate ones that designed and produced electronic control instruments and systems for manufacturing processes; small motors and gear motors used in products such as vending machines, antennas and X-ray machines; electronic and pneumatic controls for aircraft and marine operations; and electrical and electronic controls for engine-powered systems.

In the late 1920s, the Experimental Department began conducting experiments with temperature control instruments to be used in homes and other buildings and the Temperature Control Division was born. Over time, BARBER-COLMAN became known worldwide leader in electronic controls for heating, ventilating and air conditioning. These are the products that continue its name and reputation today.

The death of founder Howard Colman in 1942 was sudden but the company continued to expand its

operations under changing leadership. Ground was broken in 1953 for a manufacturing building in

neighboring Loves Park IL to house the overhead door division and the Uni-Flow division. Three later additions

were made to that plant.

The divestiture of BARBER-COLMAN divisions began in 1984 with the sale of the textile division to Reed-

Chatwood Inc which remained at BARBER-COLMAN’s original site on Rock Street until 2001. The machine tool

division, the company’s second oldest unit, was spun off in 1985 to Bourn and Koch, another Rockford

company. At that time, it was announced that the remaining divisions of the BARBER-COLMAN Company

would concentrate their efforts on process controls and cutting China tools. These moves reduced local

employment at BARBER-COLMAN’s several locations to about 2200. The remaining divisions were eventually

sold as well, but the BARBER-COLMAN Company name continues to exist today as one of five subsidiaries of

Eurotherm Controls Inc whose worldwide headquarters are in Leesburg VA. The Aerospace Division and the

Industrial Instruments Division still operate at the Loves Park plant, employing 1100 workers in 2000. The

historic complex on Rock Street was vacated in 2001 and the property purchased by the City of Rockford in

2002.

Extensive documentation from the Experimental Department was left at the Rock Street plant when the

company moved out and was still there when the site was purchased by the City of Rockford. These

documents are now housed at the Midway Village Museum.

Trashed office. Abandoned Barber-Colman factory in Rockford, Illinois

Image by slworking2

History of the Barber-Colman Company

Historically one of Rockford’s largest manufacturers.

Began with the founding of the Barber & Colman Company in 1894 – partnership between Howard Colman, an inventor and entrepreneur, and W. A. Barber, an investor. [Today he would probably be considered a venture capitalist.] Colman’s first patent and marketable invention was the Creamery Check Pump used to separate buttermilk and dispense skimmed milk.

Colman’s textile production inventions led the company on its rapid rise as a worldwide leader in the design and manufacture of diversified products. Specific items designed for the textile industry included the Hand Knotter and the Warp Tying Machine China. Through these innovations, Barber & Colman was able to build its first plant on Rock Street in Rockford’s Water Power District, and to establish branch offices in Boston MA and Manchester, England.

Incorporated as Barber-Colman in 1904 and built 5 new major structures on their site by 1907.

Later innovations for the textile industry included an Automatic Winder, High Speed Warper and Automatic Spoolers. By 1931, the textile machinery division had branch production facilities in Framingham MA; Greenville SC; Munich, Germany; and Manchester. This part of the business flourished through the mid-1960s but then declined as other divisions expanded.

Branched out from the textile industry into machine tools in 1908 with Milling China Cutters. Barber-Colman created machines used at the Fiat plant in Italy (1927) and the Royal Typewriter Co. outside Hartford CT. By 1931, the Machine China Tool and Small Tool Division of Barber-Colman listed branch offices in Chicago, Cincinnati and Rochester NY.

As part of its commitment to developing a skilled work force, Barber-Colman began the Barber-Colman Continuation School for boys 16 and older shortly after the company was founded. It was a 3-year apprentice program that trained them for manufacturing jobs at Barber-Colman and paid them hourly for their work at rate that increased as their proficiency improved. The program was operated in conjunction with the Rockford Vocational School.

To foster continued inventions, an Experimental Department was established with the responsibility of continually developing new machines. A lab was first installed in 1914 and was divided into two parts – a chemistry lab to provide thorough analysis of all metals and their component properties, and a metallurgical lab to test the effectiveness of heat treatment for hardening materials. Innovations in the Experimental Department laid the groundwork for the company’s movement into the design and development of electrical and electronic products, and energy management controls.

BARBER-COLMAN became involved in the electrical and electronics industry in 1924 with the founding of the Electrical Division. First product was a radio operated electric garage door opener controlled from the dashboard of a car. Unfortunately, it was too expensive to be practical at the time. The division’s major product in its early years was Barcol OVERdoors, a paneled wood garage door that opened on an overhead track. Several designs were offered in 1931, some of which had the appearance of wood hinged doors. This division eventually expanded into four separate ones that designed and produced electronic control instruments and systems for manufacturing processes; small motors and gear motors used in products such as vending machines, antennas and X-ray machines; electronic and pneumatic controls for aircraft and marine operations; and electrical and electronic controls for engine-powered systems.

In the late 1920s, the Experimental Department began conducting experiments with temperature control instruments to be used in homes and other buildings and the Temperature Control Division was born. Over time, BARBER-COLMAN became known worldwide leader in electronic controls for heating, ventilating and air conditioning. These are the products that continue its name and reputation today.

The death of founder Howard Colman in 1942 was sudden but the company continued to expand its operations under changing leadership. Ground was broken in 1953 for a manufacturing building in neighboring Loves Park IL to house the overhead door division and the Uni-Flow division. Three later additions were made to that plant.

The divestiture of BARBER-COLMAN divisions began in 1984 with the sale of the textile division to Reed-Chatwood Inc which remained at BARBER-COLMAN’s original site on Rock Street until 2001. The machine tooldivision, the company’s second oldest unit, was spun off in 1985 to Bourn and Koch, another Rockfordcompany. At that time, it was announced that the remaining divisions of the BARBER-COLMAN Company would concentrate their efforts on process controls and cutting China tools. These moves reduced local employment at BARBER-COLMAN’s several locations to about 2200. The remaining divisions were eventually sold as well, but the BARBER-COLMAN Company name continues to exist today as one of five subsidiaries of Eurotherm Controls Inc whose worldwide headquarters are in Leesburg VA. The Aerospace Division and the Industrial Instruments Division still operate at the Loves Park plant, employing 1100 workers in 2000. The historic complex on Rock Street was vacated in 2001 and the property purchased by the City of Rockford in 2002.

Extensive documentation from the Experimental Department was left at the Rock Street plant when the company moved out and was still there when the site was purchased by the City of Rockford. These documents are now housed at the Midway Village Museum.

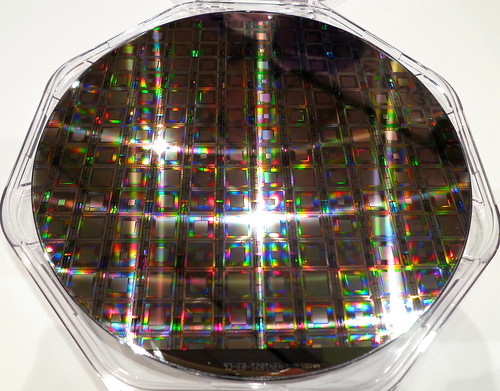

Hot off the press — the latest D-Wave wafer of quantum processors and TIME cover story

Image by jurvetson

I took this photo of the latest hot lot of processor chips of various sizes. Pretty shiny bling.

I am in the D-Wave board meeting now, and we just got a peek of next week’s TIME Magazine cover (below). And it made the Charlie Rose show.

Here are some excerpts:

"The Quantum Quest for a Revolutionary Computer

The D-Wave Two is an unusual computer, and D-Wave is an unusual company. It’s small, just 114 people, and its location puts it well outside the swim of Silicon Valley. But its investors include the storied Menlo Park, Calif., venture-capital firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson, which funded Skype and Tesla Motors. It’s also backed by famously prescient Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and an outfit called In-Q-Tel, better known as the high-tech investment arm of the CIA. Likewise, D-Wave has very few customers, but they’re blue-chip: they include the defense contractor Lockheed Martin; a computing lab that’s hosted by NASA and largely funded by Google; and a U.S. intelligence agency that D-Wave executives decline to name.

The reason D-Wave has so few customers is that it makes a new type of computer called a quantum computer that’s so radical and strange, people are still trying to figure out what it’s for and how to use it. It could represent an enormous new source of computing power–it has the potential to solve problems that would take conventional computers centuries, with revolutionary consequences for fields ranging from cryptography to nanotechnology, pharmaceuticals to artificial intelligence.

That’s the theory, anyway. Some critics, many of them bearing Ph.D.s and significant academic reputations, think D-Wave’s machines aren’t quantum computers at all. But D-Wave’s customers buy them anyway, for around million a pop, because if they’re the real deal they could be the biggest leap forward since the invention of the microprocessor. …

Physicist David Deutsch once described quantum computing as "the first technology that allows useful tasks to be performed in collaboration between parallel universes." Not only is this excitingly weird, it’s also incredibly useful. If a single quantum bit (or as they’re inevitably called, qubits, pronounced cubits) can be in two states at the same time, it can perform two calculations at the same time. Two quantum bits could perform four simultaneous calculations; three quantum bits could perform eight; and so on. The power grows exponentially.

The supercooled niobium chip at the heart of the D-Wave Two has 512 qubits and therefore could in theory perform 2^512 operations simultaneously. That’s more calculations than there are atoms in the universe, by many orders of magnitude. "This is not just a quantitative change," says Colin Williams, D-Wave’s director of business development and strategic partnerships, who has a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence and once worked as Stephen Hawking’s research assistant at Cambridge. "The kind of physical effects that our machine has access to are simply not available to supercomputers, no matter how big you make them. We’re tapping into the fabric of reality in a fundamentally new way, to make a kind of computer that the world has never seen."

Naturally, a lot of people want one. This is the age of Big Data, and we’re burying ourselves in information– search queries, genomes, credit-card purchases, phone records, retail transactions, social media, geological surveys, climate data, surveillance videos, movie recommendations–and D-Wave just happens to be selling a very shiny new shovel. "Who knows what hedge-fund managers would do with one of these and the black-swan event that that might entail?" says Steve Jurvetson, one of the managing directors of Draper Fisher Jurvetson. "For many of the computational traders, it’s an arms race."

One of the documents leaked by Edward Snowden, published last month, revealed that the NSA has an million quantum-computing project suggestively code-named Penetrating Hard Targets. Here’s why: much of the encryption used online is based on the fact that it can take conventional computers years to find the factors of a number that is the product of two large primes. A quantum computer could do it so fast that it would render a lot of encryption obsolete overnight. You can see why the NSA would take an interest. …

For its first five years, the company existed as a think tank focused on research. Draper Fisher Jurvetson got onboard in 2003, viewing the business as a very sexy but very long shot. "I would put it in the same bucket as SpaceX and Tesla Motors," Jurvetson says, "where even the CEO Elon Musk will tell you that failure was the most likely outcome." By then Rose was ready to go from thinking about quantum computers to trying to build them–"we switched from a patent, IP, science aggregator to an engineering company," he says. Rose wasn’t interested in expensive, fragile laboratory experiments; he wanted to build machines big enough to handle significant computing tasks and cheap and robust enough to be manufactured commercially. With that in mind, he and his colleagues made an important and still controversial decision.

Up until then, most quantum computers followed something called the gate-model approach, which is roughly analogous to the way conventional computers work, if you substitute qubits for transistors. But one of the things Rose had figured out in those early years was that building a gate-model quantum computer of any useful size just wasn’t going to be feasible anytime soon. …

Adiabatic quantum computing may be technically simpler than the gate-model kind, but it comes with trade-offs. An adiabatic quantum computer can really solve only one class of problems, called discrete combinatorial optimization problems, which involve finding the best–the shortest, or the fastest, or the cheapest, or the most efficient–way of doing a given task.

This is great if you have a really hard discrete combinatorial optimization problem to solve. Not everybody does. But once you start looking for optimization problems, or at least problems that can be twisted around to look like optimization problems, you find them all over the place: in software design, tumor treatments, logistical planning, the stock market, airline schedules, the search for Earth-like planets in other solar systems, and in particular in machine learning.

Google and NASA, along with the Universities Space Research Association, jointly run something called the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, or QuAIL, based at NASA Ames, which is the proud owner of a D-Wave Two. "If you’re trying to do planning and scheduling for how you navigate the Curiosity rover on Mars or how you schedule the activities of astronauts on the station, these are clearly problems where a quantum computer–a computer that can optimally solve optimization problems–would be useful," says Rupak Biswas, deputy director of the Exploration Technology Directorate at NASA Ames. Google has been using its D-Wave to, among other things, write software that helps Google Glass tell the difference between when you’re blinking and when you’re winking.

Lockheed Martin turned out to have some optimization problems too. It produces a colossal amount of computer code, all of which has to be verified and validated for all possible scenarios, lest your F-35 spontaneously decide to reboot itself in midair. "It’s very difficult to exhaustively test all of the possible conditions that can occur in the life of a system," says Ray Johnson, Lockheed Martin’s chief technology officer. "Because of the ability to handle multiple conditions at one time through superposition, you’re able to much more rapidly–orders of magnitude more rapidly–exhaustively test the conditions in that software." The company re-upped for a D-Wave Two last year.

Another challenge Rose and company face is that there is a small but nonzero number of academic physicists and computer scientists who think that they are partly or completely full of sh-t. Ever since D-Wave’s first demo in 2007, snide humor, polite skepticism, impolite skepticism and outright debunkings have been lobbed at the company from any number of ivory towers. "There are many who in Round 1 of this started trash-talking D-Wave before they’d ever met the company," Jurvetson says. "Just the mere notion that someone is going to be building and shipping a quantum computer–they said, ‘They are lying, and it’s smoke and mirrors.’"

Seven years and many demos and papers later, the company isn’t any less controversial. Any blog post or news story about D-Wave instantly grows a shaggy beard of vehement comments, both pro- and anti-. …

But where quantum computing is concerned, there always seems to be room for disagreement. Hartmut Neven, the director of engineering who runs Google’s quantum-computing project, argues that the tests weren’t a failure at all–that in one class of problem, the D-Wave Two outperformed the classical computers in a way that suggests quantum effects were in play. "There you see essentially what we were after," he says. "There you see an exponentially widening gap between simulated annealing and quantum annealing … That’s great news, but so far nobody has paid attention to it." Meanwhile, two other papers published in January make the case that a) D-Wave’s chip does demonstrate entanglement and b) the test used the wrong kind of problem and was therefore meaningless anyway. For now pretty much everybody at least agrees that it’s impressive that a chip as radically new as D-Wave’s could even achieve parity with conventional hardware.

The attitude in D-Wave’s C-suite toward all this back-and-forth is, unsurprisingly, dismissive. "The people that really understand what we’re doing aren’t skeptical," says Brownell. Rose is equally calm about it; all that wrestling must have left him with a thick skin. "Unfortunately," he says, "like all discourse on the Internet, it tends to be driven by a small number of people that are both vocal and not necessarily the most informed." He’s content to let the products prove themselves, or not. "It’s fine," he says. "It’s good. Science progresses by rocking the ship. Things like this are a necessary component of forward progress."

Are D-Wave’s machines quantum computers?

For now the answer is itself suspended, aptly enough, in a state of superposition, somewhere between yes and no. If the machines can do anything like what D-Wave is predicting, they won’t leave many fields untouched. "I think we’ll look back on the first time a quantum computer outperformed classical computing as a historic milestone," Brownell says. "It’s a little grand, but we’re kind of like Intel and Microsoft in 1977, at the dawn of a new computing era."