A few nice custom machined parts China images I found:

Nuclear Winter in Chernobyl

Image by Stuck in Customs

HDR Pics – the most Popular Pictures you dig from my portfolio. Thanks again for the continued comments (good and bad).

Full story from the trip here – on the blog at Stuck In Customs

I spent the day in Chernobyl. One of my Kiev game dev friends hooked me up with a private tour, so I decided to go for the day to check it out. Every woman in my life told me this was a bad idea. Every man said it sounded awesome.

It was awesome, although I really usually fair better when I listen to the women.

Anyway, the day could not have been colder, but it fit with the milieu of the trip to Chernobyl. In case you don’t know or can’t remember, this is the infamous nuclear power plant that melted down in 1986; it was the worst nuclear plant disaster in the world.

I have taken a bunch of photos, but only had time to process a few of them. I’ll post more in coming weeks and months, but I have pieced these together that show a good sampling of the day.

After I made it through the 30KM security radiation zone, where Will was detained by the military for not having proper documentation (a longer story which ended with him sitting in a military bunker for four hours watching Colombo dubbed in Ukranian), I was handed over to a member of the military who took me on a personal tour of the area. We passed through the 10KM security radiation zone, and then we were well within the exclusion zone.

I paid one of the military guys and borrowed his geiger counter so I could keep track of the RADs as we moved around. More on that later.

First, we stopped in Pripyat, a fascinating place right out of the Day After. Pripyat was built as the ultimate Soviet communist panacea, a place for Chernobyl plant workers and their families to live, go to school, play, and live their lives in master-planned bliss.

Pripyat was immediately deserted after the accident – kids left schools with their books still on the desks, families rushed out without getting everything, just complete and instant desertion. While I was there, it was completely quiet, and it was extra surreal with the early 80’s styling of the Soviet buildings, windows ajar, stuff still sitting in all the windows.

First, from Pripyat, here was the shining star of the city, the fine hotel in its Russian splendor, now an empty, cold, and radiated husk.

Second is one of the large apartment buildings with a slowly rotting exterior. I could still hear shutters opening and closing in the wind.

Next, I went to the creepiest part of Pripyat, the playground and amusement park. This was recently completed just before the disaster. Bumper cars, swings, a ferris wheel, and other bits of abandoned toys now lay quiet and creaking in the snow. The second picture is another part of the playground, where the kids emerged from school for playtime.

We checked the Geiger counter because this area was supposed to still have a significant amount of caesium-137, which takes a good 300 years to dissipate to safe levels. It was around 0.054, so we decided to keep moving. Now we started heading for the main power plant complex. We stopped in something he called the RAD forest that had an old Chernobyl sign that was kitschy and interesting. 0.290 on the screen. He looked at me, "We should leave quickly."

Finally, I ended the the tour at the Chernobyl power plant itself. It was nerve-wracking, so I took a few shots then moved along.

On the way out, I went through three different radiation checks. Below is one of the military guys that was holding a geiger counter gun that he ran along the car and a few other things. I went inside to a special decontamination center and entered a device that looked like stripped down telephone booth / nautilus machine. I placed my hands and feet on special sensors. It said I was clean in some cyrillic word that may or may not have said I was clean. I looked at the military guy that escorted me in there and he gave me one of those Russian frowns and shrugged his shoulders as if to say, "Eh, good enough".

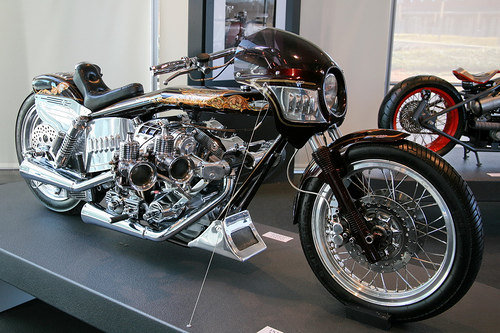

Gard Hollinger’s IlPazzo

Image by cliff1066™

The widespread notion of what a chopper looks like is Hollywood’s perpetuation of what was, essentially, a Southern California fashion statement made decades ago. The high tank and long-fork look got stuck in peoples’ minds thanks to a rash of wanton biker flicks from the ‘60s. Since then, however, the look of custom motorcycles has evolved from coast to coast and across the seas. Avant garde practitioners like Gard Hollinger have come up with many more interpretations of what “chopping” a motorcycle actually means. He coined the term retro-modernistic to describe his own style. Just as present-day musicians sample earlier recordings and embed snippets of tunes within contemporary compositions, Hollinger pays homage to older motorcycles by applying classical accents to radically engineered machines and using familiar parts in unfamiliar ways to emphasize their unconventional relationships with the rest of the bike. For instance, he will mount an automotive oil filter where you might expect to see a carburetor or fit a gas tank that looks like a lunch pail between a top tube and a motor mount. His goal is not to engineer machines agile enough to take on crotch rockets through twisty canyons; his bikes are made to turn heads, not corners. An art bike must still be roadworthy and reliable. “When you ride it, I want you to get a thrill,” says Hollinger, “I don’t want it to just be scary.”

Arlen Ness’ Untitled

Image by cliff1066™

People in the know call Arlen Ness “Godfather,” not because he makes offers you can’t refuse, but as a sign of respect for his accomplishments throughout a long and storied career. He is the patriarch of the custom motorcycle industry.

Back in “the day,” circa 1970 BC (Before Catalogs), when choppers were still the homespun products of some local dude with a torch, a hacksaw, a drill press, and a rattle can of flat black paint, Arlen Ness was going for baroque. He gold-plated parts, adorned the aluminum fascia of drive-train components with ornate engraving Chinas, and applied wild splashes of Peter Max-inspired color to the sheet metal. Plush, velour upholstery adorned his seats. If Arlen thought he could squeeze more than one motor into a frame, he would. It was nearly routine—at least for Arlen Ness—to cram two supercharged, Ironhead Sportster engines into a single frame where they would cuddle up to produce ungodly heaps of horsepower.

These eccentric-looking machines were hallmarks of early 1970s chopper style. Ness was one of the first builders to embrace the extravagant hippie counterculture that blossomed in the San Francisco Bay Area, a place Ness calls home. Some of his motorcycles from this period look like psychedelic props from a Jefferson Airplane album cover, or as if King Louis XIV of France had commissioned an eighteenth-century, rococo rocket sled to go tooling around the Palace of Versailles. Ness combined “flower power” with horsepower to create motorcycles that defined an era. He is still setting the pace for younger builders.